Breastfeeding and Birth in Bangkok Survey, 2021–2023

by Jo Cox and Iasnaia Maximo

In December 2022, the BAMBI Bumps & Babies team launched a survey to gain a greater understanding of the experiences of women giving birth and establishing breastfeeding in Bangkok.

Based on a similar survey carried out in 2016, with some new questions added related to COVID-19 and its impact on labor, delivery, and the postpartum period, our survey explored the prenatal, birthing, and postpartum experiences of mothers who delivered their babies in Bangkok between 2021 and 2023. Our questions helped us to collect data on:

- place of delivery;

- birth order;

- mode of delivery;

- to what extent the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) (1) has been adopted within the hospitals of Bangkok, specifically in regard to:

- prenatal preparation for breastfeeding;

- information and support given by healthcare professionals at the time of and after birth to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding;

- actions taken by healthcare professionals before, during, and after delivery that can impact the establishment of breastfeeding.

The questionnaire was posted on the Typeform platform and promoted through monthly birth WhatsApp groups and Facebook groups, including but not limited to The Expat Mummy Club and Thailand Babies. The final number of respondents totaled 100 women—35 who gave birth in 2021, 60 in 2022, and five in early 2023.

We will share the findings with both the respondents and the main hospitals offering maternity care, with the hope of providing helpful information to birthing families on the adoption of BFHI within Bangkok hospitals, and offering invaluable feedback to the hospitals to encourage ongoing improvement in the services offered.

Prenatal care and place of delivery

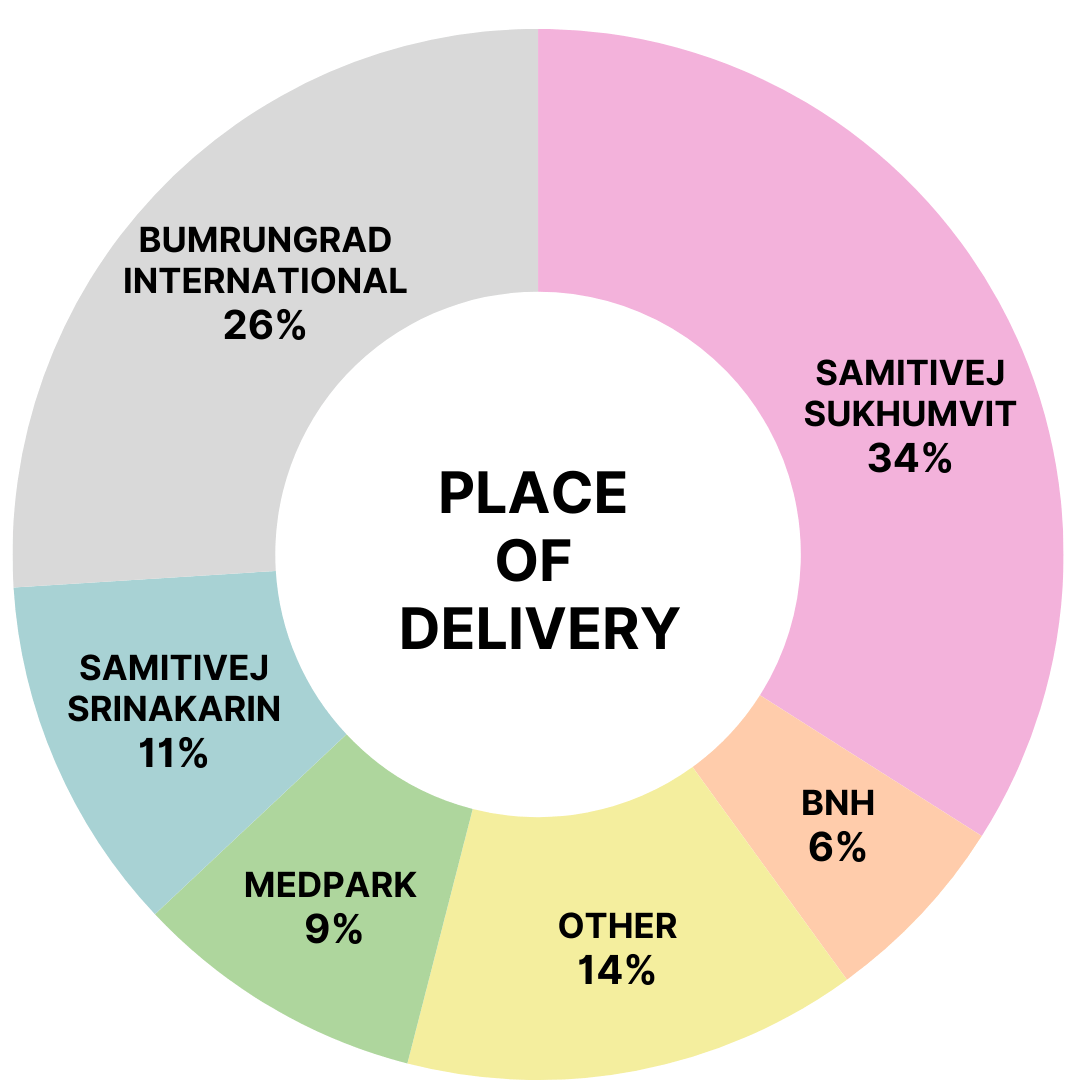

We asked women to report on all the hospitals they attended for prenatal care as well as the hospital in which they delivered. For 69 of the respondents, this was the same hospital for both prenatal care and delivery.

Twenty women, however, reported attending at least two hospitals for prenatal care. The introduction of new protocols around birth and postpartum care during the COVID-19 pandemic saw a number of obstetricians moving between hospitals to offer care. As women tend to select an obstetrician for the duration of pregnancy, a number of them chose to follow their doctors to different hospitals.

Respondents attended a total of 13 different hospitals within the city (Fig. 1). More than half of those reporting birthed in either Bumrungrad International Hospital or Samitivej Sukhumvit Hospital, the latter being the only hospital in Bangkok currently holding “baby-friendly” status. Two of the respondents experienced precipitous labor (delivery within three hours) and delivered their babies before reaching hospital.

Birth order

55% of respondents were first-time mothers while 40% were having their second child. The remaining 5% were having their third child.

COVID-19

Despite all the natural concerns expressed regarding hospital protocols and policies for COVID-19, no women reported any deviations from their planned birth resulting from a positive COVID-19 result. Very few women were affected by COVID-19 at the time of delivery.

Mode of delivery

Planned mode of delivery

Studies show that the rate of cesarean sections (CS) performed in Thailand has been on the rise for a number of years, and this is predicted to continue (2). With this data in mind, we asked our survey respondents to report on their preferred mode of delivery during their third trimester.

- 34 women hoped to deliver vaginally using an epidural for pain relief.

- 43 were aiming for an unmedicated vaginal birth.

- 20 opted for a planned CS at term.

- 3 did not report their preferred mode of delivery.

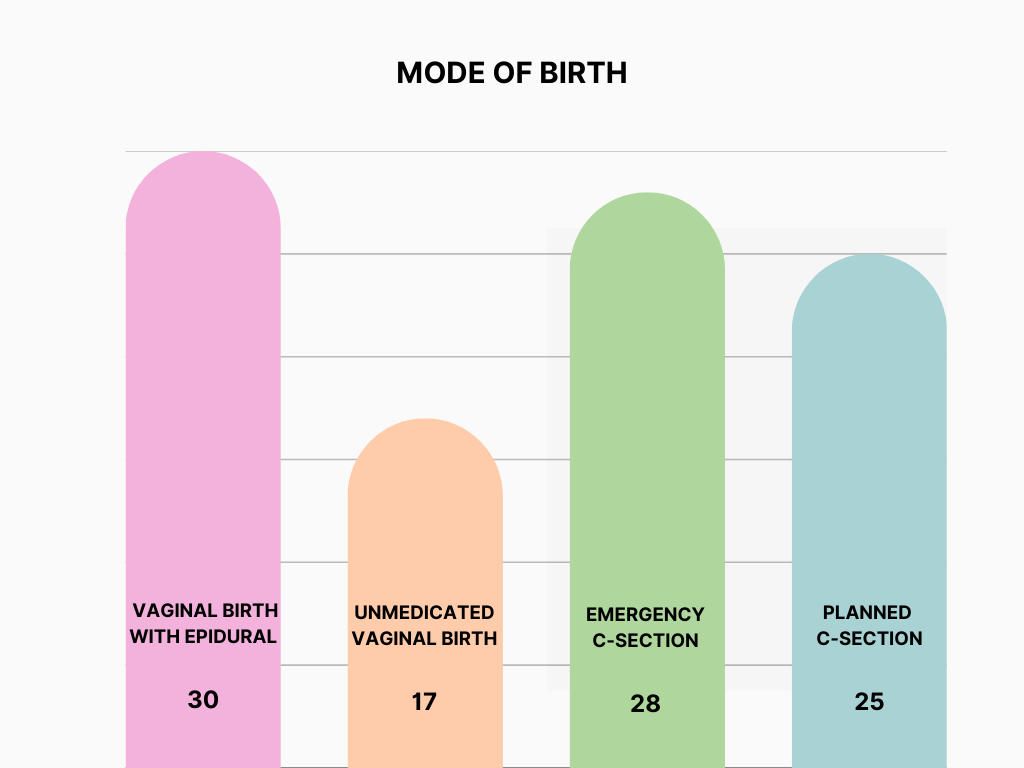

Actual mode of delivery (Fig. 2)

Among the respondents, 47 women gave birth vaginally, with 17 birthing without medication and the remaining 30 choosing epidural analgesia. The remaining 53 respondents delivered via lower segment cesarean section (LSCS).

Of the 20 women who had planned a CS, 17 delivered at term, and three required an emergency CS. A further eight women consented to CS prior to delivery for a variety of factors. The other 25 women opted for an emergency CS based on events arising during their labor. 53% of the women who delivered by CS were classified as having had an emergency CS.

The main reasons for requiring an emergency CS during labor were failure to progress / fetal distress (11 women) or an unsuccessful induction of labor (10 women). Other reasons included preterm labor, preeclampsia, and the position and size of the baby.

As well as learning the proportion of CS births to vaginal births, we were interested in finding out how mode of delivery impacted the implementation of BFHI. It is commonly understood that recovery usually takes longer following a cesarean delivery and can impact the initiation of breastfeeding, for reasons such as postponement of skin-to-skin contact while in the operating room and difficulty in finding the optimal position for latching and feeding due to post-operative pain and discomfort.

Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative

Prenatal preparation for breastfeeding

Breastfeeding policy sharing

Women were asked whether the individual hospitals’ breastfeeding policies were shared during the prenatal period—either verbally or in written form.

- 59% of women received information regarding breastfeeding policy.

- 41% did not receive any specific information.

Education on the benefits of breastfeeding

Only 38% of women were informed by staff of the benefits of breastfeeding while they were still pregnant, predominately at prenatal hospital visits.

Advice and support in hospital

Support or training in breastfeeding

Only 51% of women reported that they received any support or training in breastfeeding during their stay in hospital. Of the 49% of women not offered support, almost half were first-time moms, who may have needed additional support. Only 31% of all respondents reported feeling empowered to breastfeed their infants independently prior to their discharge from hospital.

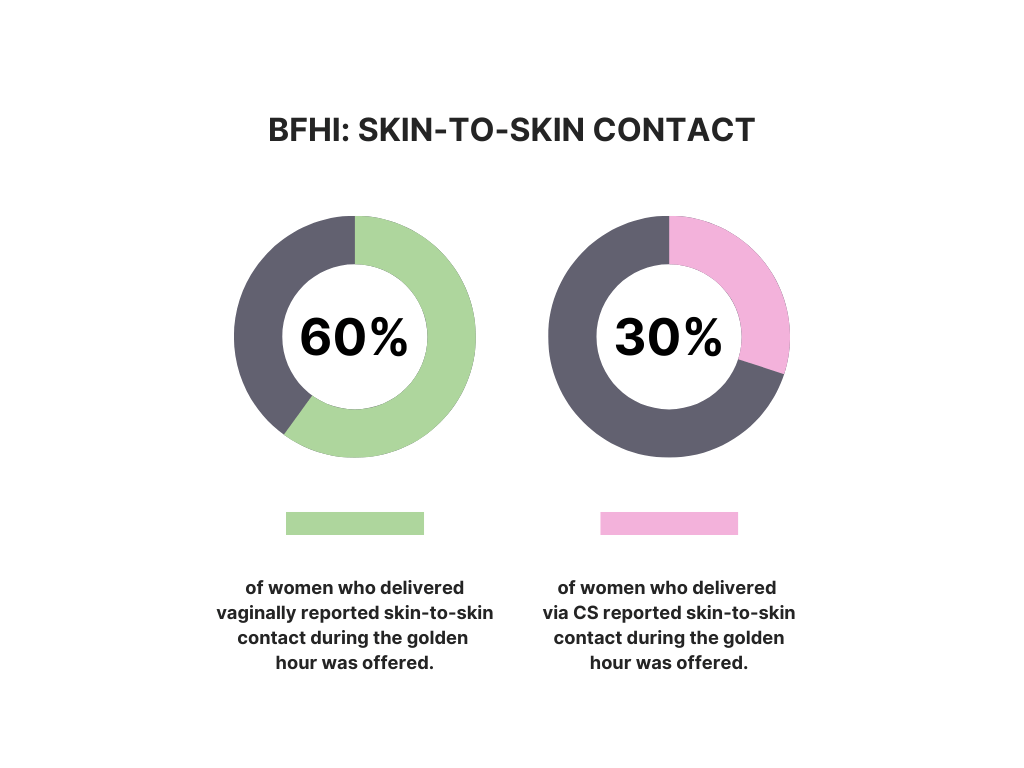

Skin-to-skin contact (Fig. 3)

Within the mother’s body, a cascade of hormonal activity is activated following the baby’s birth, initiating milk supply and production. Actions such as skin-to-skin contact and early initiation of breastfeeding reinforce these processes (3). Only 44 women were offered skin-to-skin contact with their newborn babies for the golden hour—the first hour of life when baby is extremely alert.

Among the women who delivered vaginally, 60% reported being able to enjoy skin-to-skin contact in the golden hour. The remaining 40% did not have this opportunity. For the 14% of women whose babies required immediate NICU transfer, it is clear that NICU was the priority.

Of the 56 respondents not given the opportunity for skin-to-skin contact for the first hour after birth, approximately 70% had either a planned or emergency cesarean delivery. We know that immediate skin-to-skin contact tends to be offered less routinely after CS, so it was encouraging to see that 30% of respondents who delivered by CS reported that skin-to-skin time was offered, either in the operating room, with fathers, or in the recovery unit.

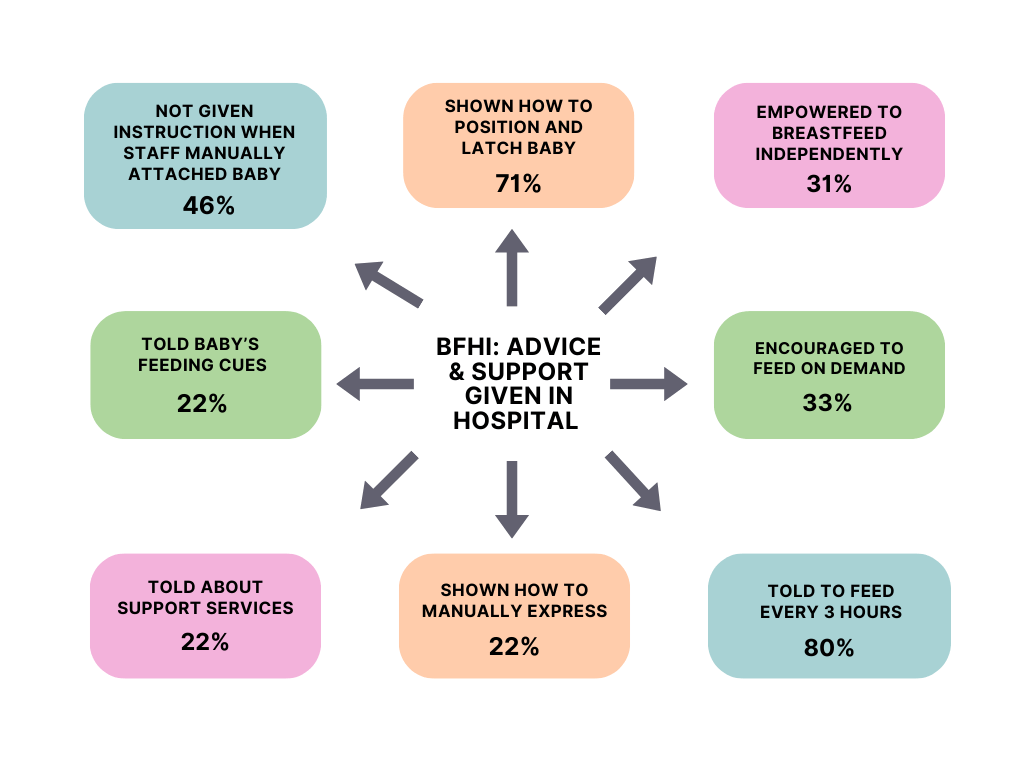

Establishing and promoting successful breastfeeding (Fig. 4)

71 women reported being shown how to correctly position and latch baby onto the breast within 30 minutes of birth; however, 44% of these mothers reported that staff would assist by attaching the infant to their breasts without explaining the principles or giving instructions on what was being achieved.

We also asked our respondents about the advice offered to them on the optimal frequency of breastfeeds. It is highly likely that a baby will demand nursing more frequently than every three hours, especially in the early days when establishing feeding. 33% of respondents were encouraged to feed their babies on demand; however, 80% of mothers reported being told by a member of hospital staff to breastfeed their babies at three-hour intervals. Conflicting advice may be misconstrued by new mothers, so it is crucial that the advice on frequency of feeds is clear and cannot be misinterpreted. If a new mother were to understand it to mean “offer a feed no longer than every three hours”, it would be less detrimental.

When encouraging on-demand feeding, it is also important to inform new mothers of the cues and signs of feeding displayed instinctively by a newborn. 22% confirmed they were given this information. The same proportion reported they had been shown how to manually express breast milk.

As the first few weeks of establishing breastfeeding can be extremely challenging, we asked our survey respondents if they had been offered advice on how to manage after being discharged from hospital. 22% of new mothers were signposted to potential external community support should any problems arise, and only 14% of all respondents were referred for lactation support, either to lactation consultation services or individual lactation consultants operating in the community.

Actions detrimental to protecting breastfeeding

We also asked our respondents a selection of questions to determine whether certain actions known to negatively impact the establishment of breastfeeding were recommended to them while in hospital. These included actions such as offering a pacifier, introducing a nipple shield, and offering supplementary feeds to the infant without it being medically indicated.

6% of new mothers were advised to offer a pacifier to their baby, 18% were advised to use a nipple shield, and 24% were encouraged to supplement their infants’ feeds with glucose or formula.

There are times when providing supplementation is medically indicated, but what is imperative is that the mother is informed as to the reason supplementation is offered and that parents consent to it. Most full-term babies are born with sufficient reserves to maintain them on minimal amounts of colostrum until the milk production / supply is established on about day three if the breasts are regularly stimulated through the infant latching. 29% of the women who reported that glucose or formula was offered to their babies were not informed of any medical reason for supplementation.

We also included a question related to the prescription of domperidone (also known as Motilium), a medicine known to be prescribed to women to stimulate their milk supply. Premature prescription of this drug potentially reinforces the insecurity that many women experience that their milk supply may be insufficient to satisfy their baby. Furthermore, using this medication to increase milk supply remains controversial as there is limited evidence to support its safety or efficacy (4). Among respondents, 29% were offered domperidone to increase their milk supply while still in hospital following delivery and before adequate time had been allowed for supply to be established.

Conclusion

Establishing, supporting, and protecting breastfeeding in the first few days is about empowering new mothers with accurate information, promoting confidence, and reassuring them as they adapt to their new role. This includes offering the opportunity for skin-to-skin contact and early initiation of feeding, encouraging feeding on demand over feeding every three hours, and advising mothers to seek support after being discharged from hospital.

The results of our survey provide a good indication of the current breastfeeding practices within Bangkok hospitals and offer an opportunity to open dialogues with healthcare providers to ensure BFHI are being implemented more widely and effectively.

We intend to repeat the survey in 2024 to track progress and are happy to provide continuous support to all pregnant women and new parents here in Bangkok.

We would like to thank all the families who contributed by filling out the questionnaire, and we hope that any specific issues that were shared will be reflected upon by the healthcare providers following our feedback.

Photos from Canva.

Tens steps to successful breastfeeding (5)

References

- World Health Organization (2020) Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services: the revised Baby-friendly Hospital initiative: 2018 implementation guidance: frequently asked questions. who.int/publications/i/item/9789240001459

- Nuampa, S., Ratinthorn, A., Lumbiganon, P., Rungreangkulkij, S., et al. (2023) “Because it eases my Childbirth Plan”: a qualitative study on factors contributing to preferences for caesarean section in Thailand. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 23(1), 280. /doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05576-8

- Moore, ER., Bergman, N., Anderson, GC. and Medley, N. (2016) Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016(11). doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub4

- McBride,G., Stevenson, R., Zizzo, G. et al (2023) Women's experiences with using domperidone as a galactagogue to increase breast milk supply: an Australian cross-sectional survey. Int Breastfeed J, 18(11). /doi.org/10.1186/s13006-023-00541-9

- World Health Organization (2019) Ten steps to successful breastfeeding. who.int/multi-media/details/ten-steps-to-successful-breastfeeding

About the Authors

Jo Cox is a UK-trained nurse and midwife. Over the past 20 years, she has spent significant periods of time overseas (Asia and Africa) with MSF and the Red Cross. Jo is the current Bumps & Babies Coordinator for BAMBI and is keen to engage with the pregnant and new mums’ community in Bangkok to offer doula/midwifery care to anyone seeking support and advice.

Iasnaia, a Brazilian with a pinch of Irish, started her career as a lawyer and now dedicates her time and passion to empower and support women in all aspects of motherhood as a doula, HypnoBirthing® educator, yoga teacher, and breastfeeding counselor. Living in Thailand since July 2016, she and her German husband and their two Amsterdam home-born boys enjoy eating her way through Bangkok and beyond. She is part of the BAMBI Bumps & Babies team. To know more about Iasnaia, please visit maedoula.com.